This article was originally published on TRAFO - Blog for Transregional Research on October 31, 2019. The following is partly based on research done during the seminar Visualization of Processes of Spatialization by S. Lenz and J. Moser of IfL Leipzig.

When Richard Henry Dana Jr. visited San Francisco in 1859 after an absence of almost a quarter of a century, he was informed that, unbeknownst to him, he had become a man of considerable fame on the West Coast. As an adolescent, Dana was studying law at Harvard when he caught the measles, which led to a inflammatory condition that affected his eyesight and reading ability. Coming from a well-to-do family, to everyone’s surprise Dana decided not to take the classical route of doing some R&R in the resorts of Europe. Instead, he marched to Boston harbor and signed up as a low-ranking merchant sailor on the Pilgrim bound for Alta California via Cape Horn and the Chilean Juan Fernandez island. The notes of this trip, especially the strenuous life at sea and sadistic behavior of the ship’s captain is regarded by some critics as the inspiration for Melville’s Moby-Dick. Since the resulting novel was one of the few (and out of those, perhaps the most readable) depiction of California written in English, Dana shaped the expectations and mindscapes of scores of American emigrants and squatters who moved to the newly acquired Californian territories in the aftermath of the Mexican-American War.

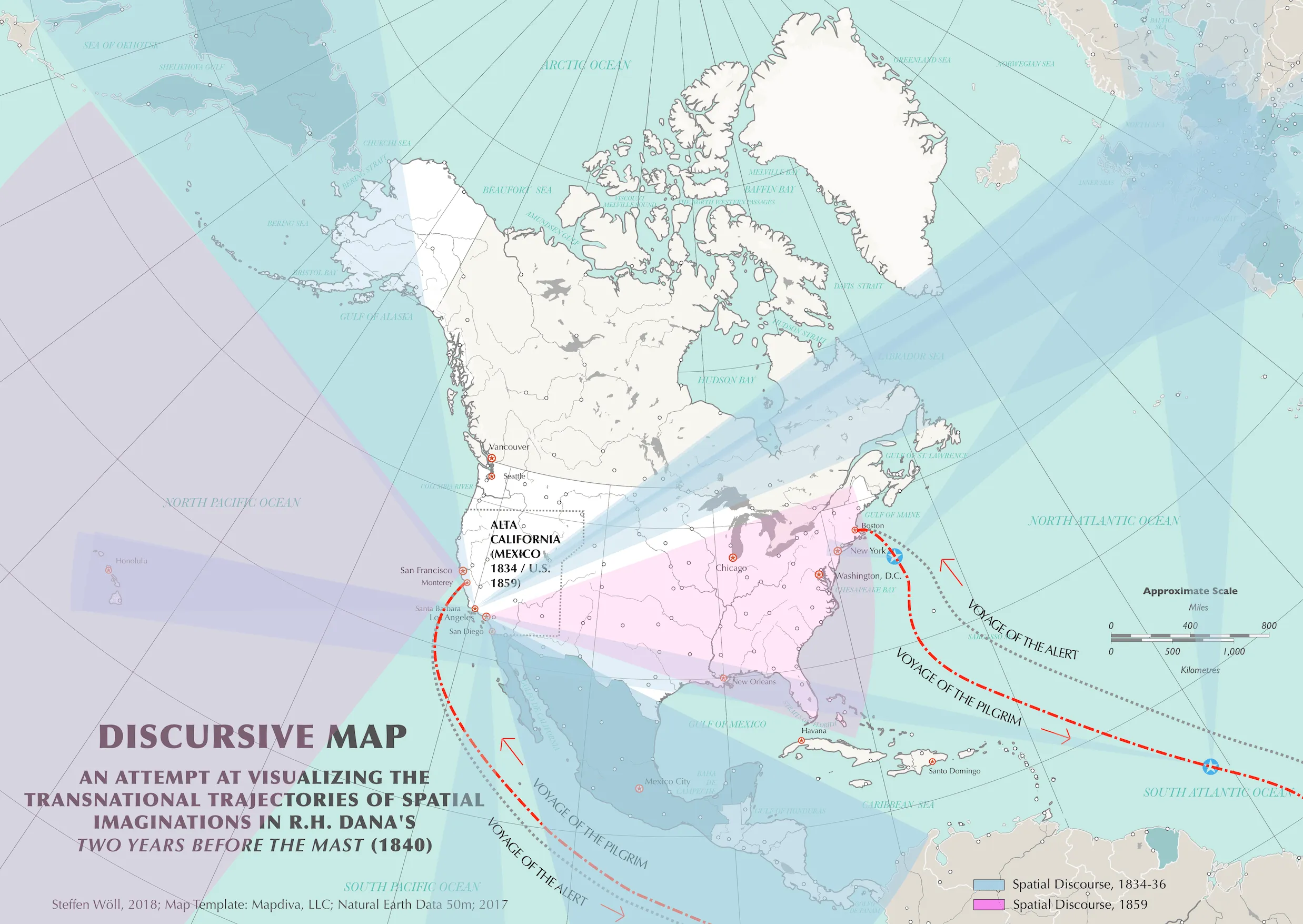

Figure: Concept of a discursive map based on Richard Henry Dana’s Two Years Before the Mast (1840).

From a perspective that is interested in both processes of spatialization in literature as well as their visualization, certain questions impose themselves:

- What kind of place-making discourses, interaction, and dynamics are at play in the text and how (if at all) can they be represented and examined in a visual manner?

- What are the benefits and challenges of such an undertaking?

- Finally, and perhaps the elephant in the room: Why on earth would one try to map literature ? On first glance, it seems unusual and even somewhat problematic to diminish the textual complexity that we as cultural and literary studies scholars are used to engage with toolsets like close reading and analytical parameters like race, class, and gender. In addition, what might be the disciplinary benefits of creating potentially reductive graphical depictions on the basis of literature? If anything, many would (and should) see this as an invitation for critiquing and deconstructing the most basic assumptions of such undertakings and, while they are at it, the epistemic groundwork of map-making in its totality as one of the oldest instruments of exerting political and/or (post)colonial power structures.

In addition to these considerations, the main methods of literary and cultural studies seem to be fundamentally incompatible, or perhaps even antithetic towards mapping and visualization as practices that are driven traditionally by the collection of empirical ‘data.’ With reference to Lefebvre’s conception of space, this problem is situated at the fault line between “representational space” (i.e., theories, ideas, affects, imaginations of space that can scarcely be represented or explained through numbers, but need be tackled narratively) and “representations of space” (i.e., data-driven models like measurements and demographics that can be more readily visualized with the help of maps). There are, however, certain exceptions to this adversity between textual/cultural dynamics and visualization, which might provide us with possibilities to visualize certain aspects of textual spatiality:

- The literal spatial narrative found within a story itself, namely the (imagined) movement of a protagonist, which can be broken down along the line of certain themes, tropes etc. Such a map would typically lose most analytical value as it does not provide any additional insights apart from parameters regarding movement and (im)mobility. This kind of mapping can be applied to both author and text and serves as a descriptive toolset for researchers to better understand certain aspects of spatiality that are connected to movement.

- As Lefebvre suggests, representational spaces are always embedded in historical contexts, therefore visualizing the historical formation (i.e., timeline) of a representational (textual) space might help to permeate it analytically. In praxis, however, such approaches carry the risk of circular reasoning and might turn into self-fulfilling prophecies as one creates a map and subsequently performs a historical reading of said map, possibly arriving at conclusions that are influenced by the bias inherent in creating the map itself, e.g. the options and limitations of visualization or GIS software.

- Finally, one could think of mapping the (inter)textual relationships regarding certain aspects of spatiality in order to reveal shared characteristics or discrepancies that might exist between certain spatial imaginations/representations either in a single text or among different texts. This approach would enable the literary cartographer to speculate about how spatialization processes interact to produce/promote/defend/attack/subvert certain imaginations of space. In my understanding, this is the most promising approach, although it is fraught with a number of challenges, notably the lack of an established hermeneutic model that could facilitate a reliable and comparable extraction and translation of text into some sort of data that would then lend itself to visualization.

One key issue in fact remains our (lack of) understanding of the concept of ‘data,’ which here cannot be seen as a generator of quantifiable knowledge (this notion must be left to the linguists), but as a flexible toolset of qualitative, interpretive, observer-dependent, experimental, and performative parameters of knowledge production. On the one hand, this is good news as the humanities certainly provide myriads of analytical lenses with a seemingly endless combinatory potential. On the downside, this notion might also be the coup de grâce to any hopes of a common visual language or methodology in the emerging field of literary mapping: The horror vacui of methodological emptiness hence continues.

The latter stance towards literary mapping could be termed ‘conceptual mapping’ and emphasizes the production of individual maps that exist independently and discretely by the rules of their own methodology. These maps are experimental in form and scale and depict ‘soft’ (topical, thematic, narrative, allegorical, metaphorical etc.) ‘data’ rather than formalized depictions of ‘hard’ empirical ‘facts.’

The map shown above should be viewed as a conceptual, experimental implementation of these considerations using the example of spatial discourse in Dana’ Two Years Before the Mast. The blue beams represent key spatial imaginations found in the text during the Pilgrim’s voyage from Boston to California, as well as during Dana’s stay at the coast between 1834-1836 during which he was occupied in loading, unloading, and processing animal hides, and in his spare time recorded aspects of social life in various towns that then were still a part of Mexico. These blue ‘discursive beams’ appear quite eclectic, global, and transnational in their outreach, revealing the imagined connections of California to many locations on the globe. From a technical standpoint, I used the program Ortelius 2 and a layered SVG file (many of which are available for free online) as a basis, removing most preset layers such as contemporary nation and state borders, yet keeping intact key topographic features like important rivers and bodies of water. One of the issues here was that working with historical texts, it is very challenging to find templates that include correct historical outlines of countries, which is one of the major flaws of this map, which I tried to mitigate by at least adding the rough outlines of the historical region of Alta California as it existed in 1834. The only solution for this would be to create a custom map, which of course poses a quite demanding task that requires time and considerable expertise, both of which I am sadly lacking. Instead, I used teal color to indicate the reference points of spatial imaginations, i.e. the endpoints of the beams. In addition, I chose to make the beams semi-transparent in order to showcase discursive overlaps and concentrations.

This, however, exposes the main flaw of using beams or cones, a design I intended to function as a visual metaphor for imaginary fields of vision the text ‘sends out’ to certain places and regions. In an unfortunate side effect, the cone shapes overlap at certain areas, which becomes misleading or at least confusing for the viewer. For instance, the areas with the darkest shade of blue, per my definition those with the highest concentration of spatial discourse in the text, appear to be located around the Celtic Sea and Bay of Biscay. Both, however, are never actually discussed in the novel. It has been suggested that another form language such as using straight lines might solve this problem. But this in turn would negate the (arguably) central insight conveyed by this map, namely the scalar contrast of the blue and the purple cones. The latter represent the ways in which Dana imagined California during his second visit in 1859 and suggest a pronounced shift of attitude towards the role of the region in a national and global context. The records of his encounters during his time as a sailor discursively format the Californian and Mexican spaces as decidedly multi-national assemblages that were at the same time fragmented, diverse, contested, and highly interconnected with transnational and multilateral spheres, as indicated by the blue cones. In this imagination of California, Native Americans, Mexicans, Anglo-Americans, English, Scots, French, Irish, Germans, Russians, and Pacific Islanders and many others, all with their own interests and traditions, together create a shared space of socio-economic interaction whose multi-scalar composition is a source of constant fascination for the young man from Boston (a term that the Sandwich Islanders (i.e., today’s Hawai’i) use synonymous with the United States). Working at the fur company’s hide house at San Pedro Beach, Dana notes that

We had now, out forty or fifty, representatives from almost every nation under the sun, two Englishmen, three Yankees, two Scotchmen, two Welshmen, one Irishman, three Frenchmen (two of whom were Normans, and the third from Gascony), one Dutchman, one Austrian, two or three Spaniards (from old Spain), half a dozen Spanish-Americans and half- breeds, two native Indians from Chili and the Island of Chiloe, one negro, one mulatto, about twenty Italians, from all parts of Italy, as many more Sandwich-Islanders, one Tahitian, and one Kanaka from the Marquesas Islands.

A conversation with the Pilgrim’s African American cook gives further insights into the resulting trajectories of transnational and multi-ethnic discourse. For instance, at one point in the book the cook asks Dana:

[Y]ou know what countryman ‘e carpenter be?’ ‘Yes,’ said I; ‘he’s a German.’ ‘What kind of a German?’ said the cook. ‘He belongs to Bremen,’ said I. […] ‘I was mighty ‘fraid he was a Fin […].’ I asked him the reason of this, and found that he was fully possessed with the notion that Fins are wizards, and especially have power over winds and storms. […] He had been to the Sandwich Islands in a vessel in which the sail-maker was a Fin, and could do anything he was of a mind to.

However, after his return 24 years later, Dana euphorically describes a total transformation of San Francisco from what he knew as a picturesque, multi-ethnic village to what he now embraces as the capital of “the sole emporium of a new world, the awakened Pacific.” This transformed and discursively reduced understanding of S.F. and California in general now has only two main reference points, as depicted through the purple cones: On the one hand the American nation-state, of whom it is a ‘proud’ and important yet passive agent. On the other hand the Pacific world, whose markets and resources it makes accessible, again, for the American nation-state. Santa Barbara too suddenly becomes “a part of the enterprising Yankee nation, and not still a lifeless Mexican town.” This change and reduction of spatial imaginations then might be the main insight imparted by this conceptual ‘discursive map.’ Still, the question remains: What does this attempt of visualization contribute to written analysis, especially considering the fact that the map can hardly function on its own without additional interpretive information? At this point, the best course of action, I believe, is to step back and open the subject for critical discussion and creative input from those who have read and/or analyzed the novel, but of course also geographers, cartographers, humanities scholars, and everyone interested in the mapping of spatio-literary geographies.